THE BRAIN DRAIN OF AFRICAN CLERGY

By Fr. Casmir Odundo

1.0 The Notion of Brain Drain

1.0 The Notion of Brain Drain

The

term brain drain is believed to have been coined by the Royal Society to describe the emigration of “scientists and

technologists”

to North America from post-war Europe. However, other scholars link this term to the United

Kingdom where it was used to denote the influx of Indian scientist and

engineers.

It

originally referred to technology workers leaving a nation. However, the

meaning later broadened into: “the

departure of educated or professional people from one country, economic sector,

or field for another, usually for better pay or living conditions”. It is therefore the large-scale

emigration of a large group of individuals with technical skills or knowledge.

The

converse phenomenon is “brain gain”, which occurs when there is a

large-scale immigration of technically qualified persons.

Brain

drain is common among developing nations, such as the former colonies of Africa, the island nations of the Caribbean, and particularly in centralized economies such as

former East Germany and the Soviet Union.

1.1 Factors behind Brain Drain

Brain

drain is normally determined by two aspects:

i.

Countries

ii.

Individuals

1.1.1 Countries

There

are normally two countries at play hers: The emigrated country, i.e. the source

countries and the immigrated country i.e. host country. Here the reason majorly

is social environment. People opt to emigrate from their source countries

probably due to one of the following reasons:

i.

Lack

opportunities

ii.

Political

instability or oppression

iii.

Economic

depression

iv.

Health

Risks

Regarding

the host countries we single out the following as reason for emigration to

them:

i.

Rich

opportunities

ii.

Political

stability

iii.

Freedom

iv.

Developed

Economy

v.

Better

Living conditions

1.1.2 Individual Reasons

Here

we single out:

i.

Family

influence, for instance the case of overseas relatives

ii.

Personal

preference, for instance preference for exploring or ambition for an improved

career

1.2 Demerits of Brain Drain

Brain

Drain is an economic cost, since emigrants usually

take with them the fraction of value of their training sponsored by the government or other organizations. Brain drain is also often

associated with de-skilling of emigrants in their country of destination, while

their country of emigration experiences the draining of skilled individuals.

1.3 Historic Examples of Brain Drain

|

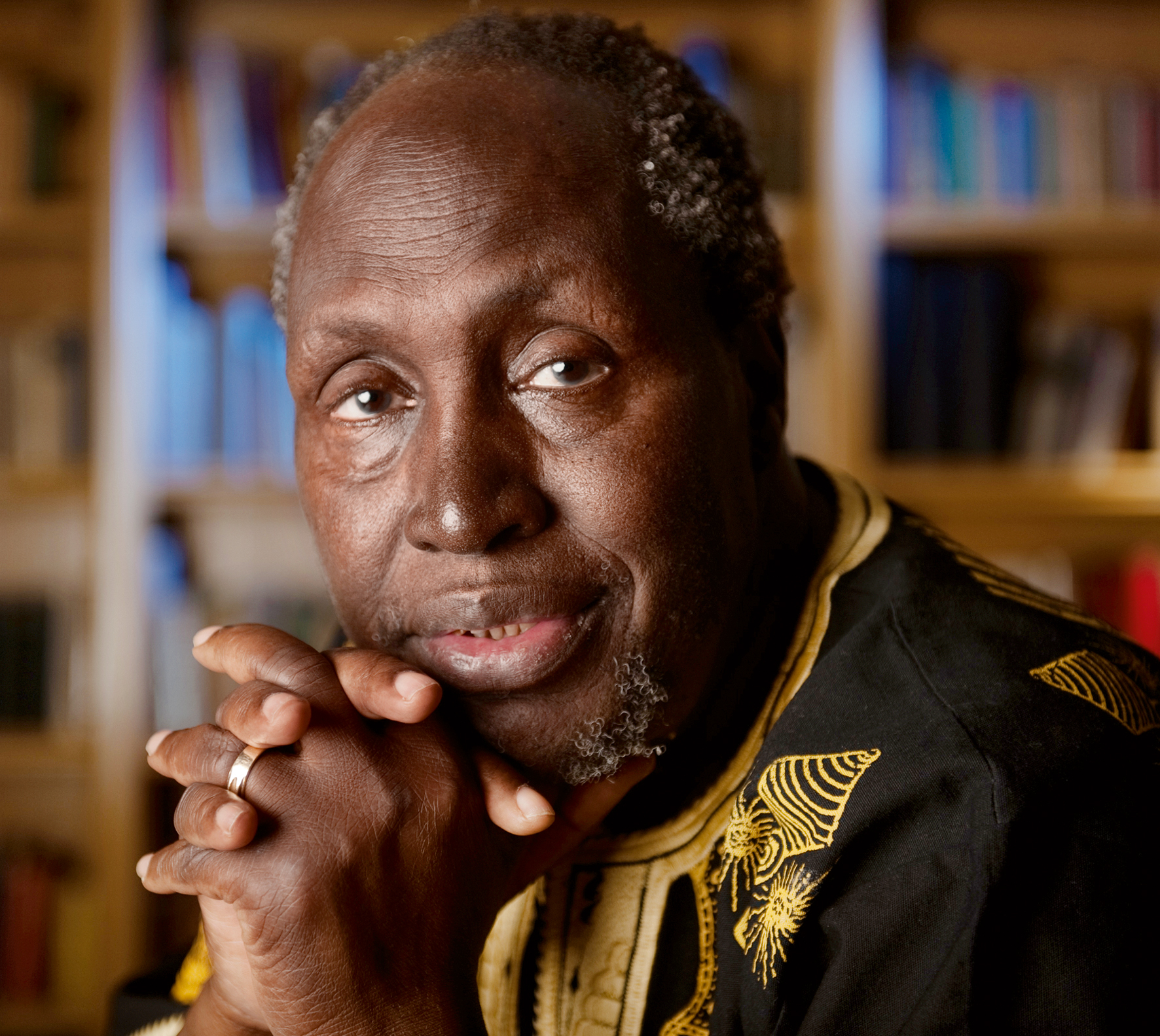

| Ngugi wa Thiong'o: A Kenyan Scholar who migrated to the US |

i.

Albert Einstein (emigrated permanently to the United States in 1933)

ii.

Sigmund Freud (He finally decided to emigrate permanently with his

wife and daughter to London, England in 1938, 2 months after the Anschluss)

iii.

Enrico Fermi (1938; though not Jewish himself, his wife Laura was)

iv.

Niels Bohr (1943; his mother was Jewish)

v.

Theodore von Karman

vi.

John von Neumann and many others

1.4 Impact of Brain Drain in the

World

1.4.1 Impact in Europe

Europe

has been hit hard by emigration of its human resource to other continents. In

2006, over 250,000 Europeans emigrated to the United States (164,285), Australia (40,455), Canada (37,946) and New Zealand (30,262). Germany alone saw 155,290 people leave the country (though

mostly to destinations within Europe). It is said that more than 500,000

Russian scientists and computer programmers have left the country since the

fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The European Union in due notice of the above

fact has introduced certain incentives to counter this outflow among them being

a "blue

card" policy

– much like the American green

card – which "seeks to draw an

additional 20 million workers from Asia, Africa and Latin America in the next

two decades".

1.4.2 Impact in Sub-Saharan Africa

Countries

in Sub-Saharan Africa have been most affected by brain drain. They have lost a

tremendous amount of their educated and skilled populations as a result of

emigration to more developed countries, which has harmed the ability of such

nations to get out of poverty. Conservatively speaking, "Brain drain has

cost the African continent over $4 billion in the employment of 150,000

expatriate professionals annually." The countries mostly hit by this

phenomenon are Nigeria, Kenya, and Ethiopia. Ethiopia for instance according to the United

Nations Development Programme, (U.N.D.P) lost 75% of its skilled workforce between 1980

and 1991. In particular, the country produces many excellent doctors, “but there are more Ethiopian doctors

in Chicago than

there are in Ethiopia.”

This sad state of affairs have made many African leaders to speak out. In his 'African Renaissance' of 1998 the then South African President Thabo Mbeki

called for all emigrated sons and daughters of Africa to come back home, He said:

"In our world in

which the generation of new knowledge and its application to change the human

condition is the engine which moves human society further away from barbarism,

do we not have need to recall Africa's hundreds of thousands of intellectuals

back from their places of emigration in Western Europe and North America, to

rejoin those who remain still within our shores! I dream of the day when these,

the African mathematicians and computer specialists in Washington and New York,

the African physicists, engineers, doctors, business managers and economists,

will return from London and Manchester and Paris and Brussels to add to the

African pool of brain power, to enquire into and find solutions to Africa's

problems and challenges, to open the African door to the world of knowledge, to

elevate Africa's place within the universe of research the information of new

knowledge, education and information."

It

is also important to note that Mbeki’s dream of a return of emigrated sons and

daughters may soon be realized as the African brain drain has begun to reverse

itself. This is probably due to rapid growth and development in many African

nations, and the emergence of an African middle class. Between 2001 and 2010,

six of the world's ten fastest-growing economies were in Africa, and between

2011 and 2015, Africa's economic growth is expected to outpace Asia's. This,

together with increased development, introduction of technologies such as fast

Internet and mobile phones, a better-educated population, and the environment

for business driven by new tech start-up companies has resulted in many

expatriates from Africa beginning to pack their bags ready to return to their

home countries, and more Africans staying at home to work.

1.6 Merits of Brain Drain

The

country of origin exporting their skilled and highly educated workforce benefit

from a brain gain both in terms of the increase in the labour power they

possess, but also in the fact “skilled migrants leaving the country generate increased

demand for higher level education amongst the population.” Furthermore, the sending back

of remittances increase economic development in the country and standard of

living. Circular migration presents a number of benefits

associated with brain drain. First, the economy of the origin country may not

be able to take advantage of the skilled laborers, so it becomes more

beneficial for the workers to migrate and send back remittances. Second, when the migrant workers return home as part of

the circular pattern, they may bring with them new skills and knowledge.

1.7 Demerits of Brain Drain

Brain

drain usually involves the loss of human capital i.e. skilled labour force who

are vital to the development of society and the country as a whole. Again the

more pressing issue skilled migrants face in contemporary society is “double marginalisation”, where migrants

are kept from integrating into their new surroundings either by society or by

existing governments, and upon their return home are shunned by the community

they originally migrated from due to their earlier departure. This “double marginalization”

has become a common feature in contemporary society, which has in some respects

reduced the amount of skilled migration occurring.

Further,

the assumption that "skilled workers

migrating are likely to increase remittances to the home country", is

not always the case. Graeme Hugo, argues that "highly skilled workers are often able to bring immediate family with

them so they are not obliged to send money back", making the

brain drain highly problematic for society especially when countries invest so

much on it.

2.0 BRAIN DRAIN OF AFRICAN PRIESTS

2.1 The reverse mission

For generations

in Africa the term "missionary" was a synonym for ‘Mzungu’. Thousands of European Catholics left Europe for the wilds of Africa, braving

heat and disease to bring the message of Christ to heathen animists. But

today's missionaries are working in the opposite direction. They're native

Africans who talk about healing the secular sickness of the West. And these

Catholic Africans are crossing the oceans in unprecedented numbers to return

the favor Western missionaries once paid them. They have a saying: `Africa has AIDS, but North America and

Europe has theological AIDS,'"

Philip Jenkins, a professor of religious

studies at Penn State who studies Christianity in developing nations

says:"Our continent's being

devastated by one thing. Yours is being devastated by another." The

growth of what scholars call "reverse

mission" fits like a puzzle piece into another trend in the Western

church: What was once a steady stream of young men being trained in the

priesthood by American and European seminaries has slowed to a trickle. More

parishes are going without priests - 3,100 in the U.S. in 2015 up from 500 in

1965. The men arriving from the developing world fill a need. According to a recent report 10% of priests in Germany now come from the developing countries. "The Europeans came to evangelize us, and we

thank them for it, now it is our turn to evangelize them. We have something to

give." Said Mr. Osigwe, a major seminarian in Nigeria nearing his

ordination to Catholic priesthood.

Seminaries

in Africa are recruiting much more candidates than their North American and

Europe counterparts. For instance Osigwe’s seminary, St. Bigard’s Memorial Seminary in Nigeria is the

largest Catholic seminary in the world, enrolling more than 1,000 young men. In contrast

the Diocese of Dallas' Holy Trinity Seminary in Texas

has its enrolment at 30 in the year 2015. This is by no means unusual for an American seminary.

Young men in America, for whatever reasons, largely don't want to be priests

any more. According to church statistics, the number of Catholics in America

increased 29 percent during the papacy of John Paul II. But the number of

priests dropped 26 percent. And a large number of the priests who remain are

elderly, or baby boomers edging closer to retirement. "If the trends continue this way, it's

obvious that the numbers will not meet up with the demand," said the

Rev. Michael Duca, Holy Trinity's rector.---Church officials say there are three

basic ways the priest shortage is being met.

i.

One is a reorganization of priestly duties -

allowing laypeople to take over some of the duties traditionally assigned to

priests, like church administration and certain ceremonial roles.

ii.

Grouping up parishes or churches into a family of churches

iii.

The other solution is importing priests from

overseas.

It is the third option that is already at play with already about one of every six

priests working in America today is foreign-born, a number that is steadily

increasing. Most of these are fished from developing countries like Vietnam,

the Philippines, India, Colombia and African countries especially Nigeria.

2.2 Why Africa Has More Vocations

This is a

question that most sociologists of religion, religious leaders really differ

about. For most Africans, they feel that Africa has many vocations doe to their ‘notorious religiousness’ as the Theologian John Mbiti put it. This is well captured by Rev. Fr. John Okoye, Bigard's rector: "We in Nigeria are naturally religious, the

instinct is in our blood. We have a reverence of the unknown."

Others

trace this phenomenon to historical reasons. According to them, African Traditional

religious leaders were held in high regard before the Christian missionaries

came, and that status transferred easily to priests when the population

converted.

However,

many contend that it might be the economic advantages that take some to

priesthood. Rev. Damian Nwankwo, a professor at Bigard says "When the Irish came, they brought roads, electricity,

schools, and people regarded them as visible gods.---When a young man is

ordained in Igboland, it is tradition that his village collects money from its

residents and buys him a car - an enormous gift in a poor nation. Priests can

afford luxuries, like satellite television, that other Nigerians only dream of.”

This fact is also alluded to by a

future priest, seminarian Tony Ezekwu, he says: "When you are a priest, you don't lack, they have a high standard of

living. People want that."The promise of status no doubt attracts some

to the priesthood. "What is their

motivation for joining the priesthood?" Asks Dean Hoge, a sociology

professor at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.. "In the best and most noble case, they want

to serve Jesus Christ. But maybe they also want to escape the farm. I'm sure

both of those are there."

It is also

noted that some young men see seminary more as a path to an education. Their

view is summed up in the comment of a young Bigard seminarian who said he was

willing to be a parish priest when he's ordained in a few months, "but what I really want to be is a professor."And

while many priests go to America and Europe because they believe they can do

good work, others come for more prosaic reasons.

2.3 Clerical Brain Drain

If it is

true that some young men join priesthood for economic reasons, then it is also

true that the reason why most of them want to go to the United States and

Europe is purely economic. Dean Hoge, estimates that an African’s priest's

buying power increases five fold when he lands in America. He links the

emigration of African priests to America with desire for wealth. He argues that

if you consider the numbers, Africa needs by far more priests than America. He

says:

“For as bad as the priest shortage is in America,

it's far worse in many emerging countries with an exploding Catholic population

- including some that are shipping priests right and left to the States. Even

with its drop in ordinations, the United States had one priest for every 1,375

Catholics in 2002. There was one for every 4,694 African Catholics. That's not

news to priests in Nigeria.”

That the

African church is in need of human resource in terms of priests is evident. "We have almost 10,000 men and women and

children in this parish," said the Rev. Humphrey Ani of St. Joseph's

Catholic Church in Enugu, Nigeria. "There's

no way we can minister to them all. We need more priests, too." In the United States, in many other places in Nothern America and in Europe rarely do you find, despite the shortage of priests, many Christians going without Mass. However, the case is different in Africa even with its seeming booming vocations. There are many parishes with over 20 other churches (outstations) with merely one or two priests. Very Many African Catholics go without the obligatory Sunday Mass. While Europe and America are witnessing a decline in clergy, many African dioceses are also witnessing the same, and in places where they are many vocations, such are still not enough to serve the rapidly growing numbers of her christians. Again, it is not completely true that there are no vocations in North America or Europe. Recently, in May 2019, the diocese of Kakamega in Kenya ordained 12 new priests, 11 of whom are diocesan. A great harvest of priests indeed. But the Archdiocese of Washington, in the United States also ordained 10 new diocesan priests a week ago. The Archdiocese of Boston in the United States on May 19th 2019 ordained 13 new priests. These factors make one question the great emigration of African priests to these foreign countries. Why are we "exporting" our priests yet we are also in dire need?

But the

exodus continues, perhaps, primarily for financial reasons, according to Hoge. The following could be the reasons behind the

financial emigration.

i.

Individual priest’s desire for individual financial

gain

ii.

Poor countries inability to support the same number

of priests as rich ones

iii.

Better organization of Catholics in rich countries

are better organized which do a better job of pressuring church leadership to

hire more priests.

The Holy

See, i.e. Vatican also seems to have acknowledged some of these issues. In 2001, Cardinal

Jozef Tomko, head of the church's Congregation for the Evangelization of

Peoples, (Propaganda Fide) wrote that the church must "counteract the prevalent trend of a certain

number of diocesan priests who ... want to leave their own country and reside

in Europe or North America, often with the intention of further studies or for

other reasons that are not actually missionary." Cardinal Tomko said

some African and Asian dioceses were sending most of their priests to work

abroad, in part because they could not be supported financially in their native

countries. He warned that Western nations (dioceses) "must never deprive young churches of these priests. ... It is a matter

of fairness and of ecclesial sense."

2.4 Challenges

In praise of African Priests working in the

United States Christopher Malloy, an assistant professor of theology at the

University of Dallas concluded: "The African church is in touch with the raw

elements of humanity: birth, marriage, death, hunger, thirst, For me, in a

comfortable house, it's easy to think life is not dramatic. They bring the

message to us with excitement."

But that

message does not always translate easily. The Africa Priests emigrants have

many problems. The first difficulties is gaining entry to America and European

countries. Tighter immigration standards after Sept. 11, 2001, have made it

more difficult for some priests to get visas.

Another

difficulty comes during screening; it's a struggle for American dioceses to

check into a foreign priest's background - a high priority for many church

leaders in the wake of accusations of priestly misconduct. "I need to make sure he's the right person,

and that can be difficult from so far away," said Father Josef

Vollmer-Konig, director of vocations for the Dallas Diocese. He said his

diocese gets one or two requests each month from Nigerian priests wishing to

work in the Dallas area, few of which are granted. Another difficulty is that

in some places White parishioners may be uncomfortable with an African priest.

Some priests also have trouble fighting through the accents and "Americans aren't very tolerant of these

things," according to Hoge. Another difficulty is that some of these

African priests have trouble adjusting to the less exalted status American

priests have - both in society and in their churches, where U.S. lay leaders

often take on decision-making roles reserved for clergy in other countries.

However, the

biggest adjustments are often ceremonial. African Masses feature hours of

singing, swaying and dancing. Western masses are, well, dull in comparison. "When I came here, I asked: If I was a

layperson, would I be going to church at all?" said the Rev. Ernest

Munachi Ezeogu, a Nigerian-born priest who now works in Toronto. "The answer was no. There is no life, no joy.

People come to fulfill a duty, not because they want to celebrate Christ."

Father Ezeogu has tried changing things a bit: adding music, adding jokes to

his homilies, trying to relate Scripture more directly to people's lives. He's

also started a Web site where priests who want livelier homilies can download

some of his. He said the reaction has been positive. But not every African

priest has had such luck. The Rev. Joseph Offor, a parish priest in Enugu, did

missionary work for several years in Germany. Once, he said, a woman approached

him before Mass and asked how long his sermon would be. "She said I should keep it to under four

minutes." (Africans are accustomed to homilies lasting an hour or

more.) "I ended up speaking for

about 15 minutes," he said. "She

was very annoyed afterward. She said she would not come back, and she did not.

It is a very different world there."

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

ALLEN, Jnr, John, “Foreign Priests and the risk of Plunder,” in The National Catholic Reporter, Feb 26, 2010.

BENTON,

Joshua, “African Priests want to fill need-if Americans let them,” in The Dallas Morning

News, January 31st 2004.

BOERI,

Tito, Herbert Brücker, Frédéric Docquier, and Hillel Rapoport (eds) Brain Drain and Brain Gain: The Global

Competition to Attract High-Skilled Migrants, Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 2012.

KAPUR,

Devesh; McHale, John. “Give Us Your Best and Brightest” The Global Hunt for Talent and Its Impact on the Developing World:

Center for Global Development: Publications". Cgdev.org. 2005.

CHRISTIANO,

Kevin J., et al., Sociology of Religion:

Contemporary Developments, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers,

2008.

STRAUBHAAR,

Thomas "‘International Mobility of the Highly Skilled: Brain Gain, Brain

Drain or Brain Exchange". HWWA

Discussion Paper 88: 1–23, 2008.

Compiled by Rev. Fr. Casmir Odundo, Parochial

Vicar, St. Veronica, Keringet Parish, Diocese of Nakuru

This is a very rich piece Fr. Casmir. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the insight Padre... nice work.

ReplyDeleteNice piece Padre

ReplyDeleteAn eye opener Abba Casmir

ReplyDeleteThanks be to God

ReplyDeleteThis is a very interesting article. Thank you Fr. for the insights.

ReplyDelete